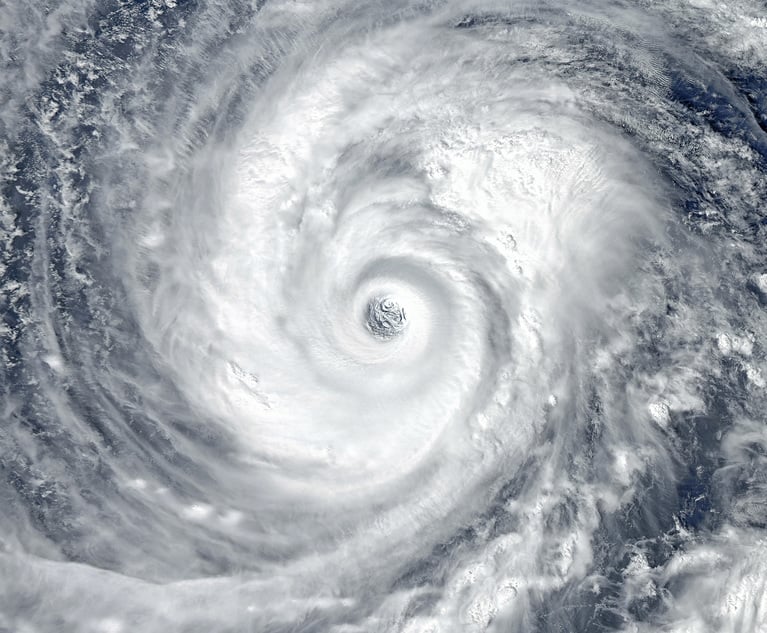

Hurricane season is a reminder of the lessons insurers havelearned from major events such as Hurricanes Katrina and Ike andSuperstorm Sandy.

|Each year, the insurance industry invests significant time andresources to prepare risk models and provide insureds with the mostsophisticated crisis response plans based on thoselessons — but are they doing enough?

|The NationalWildlife Federation and Allied World Assurance Co. Holdings teamedto find the best examples of natural or nature-based features beingused to protect communities against flooding and other naturaldisasters. In a report titled "Natural Defenses in Action," a dozen examplesfrom across the United States are highlighted.

|According to Scott Carmilani, president and CEO of Allied World,and Collin O’Mara, president and CEO of the National WildlifeFederation, the report is meant to motivate the insurance industryto encourage policymakers to use similar nature-based riskreduction across the United States.

|For example, the report calls for the industry to encourageCongress to reduce National Flood Insurance Program subsides thatincentivize development and redevelopment in high risk,environmentally sensitive areas, as well as reward communities thatdeploy nature-based risk reduction with lower NFIP rates.

|"Together, we can work with policymakers to not only decreaserisk to local communities and save taxpayers money, but also createenduring benefits for fish and wildlife, outdoor recreation andclean drinking water," says Carmilani and O'Mara.

|Here are 12 ways nature is being used to protect against naturaldisasters in the United States:

|Click here to view our full coverage on disasterrisk and recovery for Hurricane Season 2016.

||

Dauphin Island, Alabama, afterHurricanes Ivan and Katrina. (Photo: Getty)

|Preserving barrier islands on Alabama’s Gulf Coast

Found along the Atlantic and Gulf coastlines, barrier islandsbuffer many parts of the mainland from the power of the open ocean.However, these sand banks are also highly valued as oceanfrontproperty — making them a risky spot for homeowners anddiminishing the extra natural protection they offer to themainland.

In 1982, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Coastal Barrier Resources Act to preventadditional risky development on remaining intact andenvironmentally sensitive portions of barrier islands. The act waspassed to reduce threats to property and protect U.S. taxpayersfrom the burden of paying again and again to rebuild in the riskyand storm-prone areas. Savings to federal taxpayers from 1983through 2010 are estimated at about $1.3 billion, with another $200million in avoided disaster relief estimated through 2050.

|Dauphin Island, Alabama, a barrier island located three milessouth of Mobile Bay, is an example of how the act — in concertwith other federal, state and local policies — can beeffective in avoiding risks to people and property from hurricanesand coastal storms. The western spit of Dauphin Island wasdesignated a Coastal Barrier Resources Unit, and Alabama drew itscoastal construction control line to match the boundary of thefederal designation. Local officials then zoned the land asconservation and parkland, effectively prohibiting futuredevelopment.

|The effect is daunting. Since being designated, none of the landunder the Coastal Barrier Resources Act had seen new development orrequired federal assistance. In contrast, between 1988 and 2014,the 1,200 residents of Dauphin Island paid $9.3 million in floodinsurance premiums to the federal government and received $72.2million in payouts for their damaged homes.

||

A clapper rail in the marshes ofCorte Madera, California. (Photo: Len Blumin/Flickr)

|San Francisco Baylandsrestoration

Tidal marshes and other coastal ecosystems can function as naturalinfrastructure in the San Francisco Bay region, providingcost-effective protection against extreme floods and sea-level rise— the latter of which, in particular, threatens the long-termsurvival of the marshes that serve as critical natural buffers.Restoring baylands ecosystems is a multi-benefit way to offsetrising water levels and storm impacts in the future.

One effort being implemented in the region is the South Bay SaltPond Restoration Project, a combination of infrastructuremodifications and restoration of former salt ponds to tidal marsh,as recommended under the South SanFrancisco Bay Shoreline Study. The project is the largest tidalwetland restoration effort on the West Coast, and aims to restore15,100 acres of former commercial salt ponds in South San FranciscoBay to functional tidal marsh, for purposes of flood management forSouth Bay cities, habitat and public access. So far, 1,500 acres offunctional tidal marsh have been restored.

|Another project, the San Francisco Bay Living Shorelines Project, isshowing how natural features like submerged aquatic vegetation andnative oysters in the subtidal and intertidal zones can reduce waveenergy and potentially protect adjacent shorelines from erosion andstorm impacts.

||

Jean Lafayette Swamp, Lousiana,along the Mississippi River Delta. (Photo: DonnaPomeroy/Flickr)

|Restoring flows to protect coastal Louisiana

The Mississippi River Delta is the first line of defense againstthe impacts of storm surge to communities along Louisiana's coast.Construction of levees for flood protection, canals for oil and gasaccess and channels around the river's entrance for the transportof goods have had great near-term economic benefits, but came at agrave ecological cost.

These levees and channels cut off the natural flow of freshwaterand sediment into the delta, upsetting the freshwater/saltwaterbalance, and making conditions favorable for erosive forces.Because erosion and subsidence are vastly outpacing sedimentaccretion in the delta, some of the most ecologically valuablemarsh and estuarine ecosystems in the world are drowning, puttingmany coastal Louisiana communities at increased risk fromhurricanes and coastal storms.

|Penalties from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill are now a majorsource of financing for coastal Louisiana restoration through thefederal Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, TouristOpportunities and Revived Economies of the Gulf CoastStatesAct. Two linked projects exemplify new approaches toputting sediment from the river back into its delta: therestoration of the Barataria Basin Land Bridge and the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion.

|These projects are using sand from the Mississippi River'sbottom — along with silts and clays carried in its streamflow— to build new land, nourish existing marsh and help preventsaltwater from the Gulf of Mexico from penetrating into freshwatermarshes and swamps in the mid to upper reaches of the basin.

|According to the report, these projects in the Barataria Basinillustrate the kind of forwardthinking and bold vision that isnecessary to reverse years of decline and to rebuild the protectivefunctions of these ecosystems for coastal Louisiana'scommunities.

||

Taulatin National Wildlife Refugein Oregon. (Photo: Darryll DeCoster/Flickr)

|Partnering with ecosystem engineers in Oregon

In the Columbia River watershed of western Oregon, beavers are avaluable partner in taming floods, moderating water shortages,cooling water temperatures and restoring habitat for fish andwildlife. They also play a part in reducing flood risks tocommunities along the Tualatin River.

Beaver activity slows water flow and spreads water across thefloodplain, helping create habitats and wetlands. Those wetlands inturn can store excess water, increase infiltration and facilitategroundwater recharge, helping to maintain summer flows.

|A comprehensive survey of the Tualatin Basin revealed that manyheavily incised streams no longer had functional connections totheir floodplains, resulting in the decrease of native beavers andtheir preferred food sources to the area. To help restore the area,Kendra Smith, principal author of the "2005 Healthy Streams Plan," worked with citygovernments to plant native riparian vegetation, end beaverextirpation efforts and refocus trapping efforts on nutria, aninvasive mammal that can cause considerable streamside erosion.

|By 2014, the number of beavers in the area had almost doubledand their impact was clear: What had once been dense thickets ofinvasive reed canary grass had transformed into forested, healthywetlands, improving resilience against drought, enhancingbiodiversity and reducing flood risk to downstream communities.

||

Flooding from the Mississippi Riverin Grafton, Illinois, in 1993. (Photo: Liz Roll/FEMA)

|Moving out of Mississippi River floodplains

The city of Grafton, Illinois, suffers from frequent floods whenwaters rise in the Mississippi, Illinois or the even the MissouriRiver. In its 150-year history the city has flooded, on average,every two years.

In 1993 flooding from the Mississippi River submerged Graftonfor more than six months under floodwaters up to 15 feet deep. Asthe waters receded, town officials began to assess the damage: 260structures were damaged and 100 experienced damages over 50 percentof market value and were required to be elevated or were bought outand relocated. In total, 88 properties were bought out using $2.3million in Federal Emergency Management Agency Hazard MitigationGrant Program funds and $773,636 in matching funds from thestate.

|In conjunction with buyouts of damaged properties within thefloodplain, the town purchased land on top of the bluff and made itavailable for purchase by those who wished to relocate to higherground. In total, 70 homes and 18 businesses relocated out offlood-prone areas.

|While relocation is often considered a measure of last resort,it has been extremely effective at reducing risk in Grafton. In2015 the town experienced the fourth highest floodwaters in itshistory, but the relocations — combined with the decision tomaintain the riverfront as open space — meant the impact onthe town was minimal despite the absence of a levee.

||

The Cosumnes River leveebreach in California. (Photo: Lorenzo Booth/UC Merced)

|Floodplain restoration in California’s Central Valley

The floodplains of California’s Central Valley are facing growingextremes of flood and drought in the face of climate change andpopulation pressures on California’s highly managed water system.In light of such extremes of wet and dry, ecological floodplainmanagement is a cost-effective strategy that stands up to theuncertainties of future climates.

According to the report, management techniques include settingback or breaching levees to reconnect the river channel to thefloodplain in undeveloped locations; restoring marginal flood-pronefarmland to native wetlands vegetation; using floodplain easementsand water management infrastructure to reroute floodwaters arounddense urban areas; and re-creating more complex floodplaintopography in ways that increase the channel roughness to slow andcapture floodwaters, while creating or improving fish and wildlifehabitat on the floodplain.

|Such actions increase the floodplain's capacity to take onfloodwaters in places where people and property will not beaffected, thereby reducing downstream flood risk. Ecologicalfloodplain management techniques have the potential for reducingrisks of catastrophic flood losses in developed areas whilerecharging dwindling groundwater resources as insurance againstdrought and land subsidence.

||

A living shoreline protected by theDelaware Estuary. (Photo: Josh Moody/Partnership for the DelawareEstuary)

|Creating living shorelines in the Mid-Atlantic

Landowners in the Mid-Atlantic are increasingly taking greenerapproaches to shoreline stabilization, known as "livingshorelines."

The Partnership for the Delaware Estuary definesliving shorelines as a "method of shoreline stabilization thatprotects the coast from erosion while also preserving or enhancingenvironmental conditions." The concept of living shorelinescaptures a variety of shoreline stabilization techniques that usesite-appropriate, native biological materials, taking ecologicaldynamics, tides, currents and wave energy into consideration.

|The Chesapeake and Delaware bays are some of North America'smost productive aquatic habitats, but they also are quitevulnerable to the impacts of climate change, sea-level rise andlong-term land subsidence. In particular, the combination ofextreme storm events and sea-level rise is having dramatic effectson communities lining these areas from erosion and flooding, andleading to accelerated land loss. As an alternative to thetraditional methods used to slow erosion (such as sea walls),communities have been developing living shorelines to protect theshorelines.

|In 2007 the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, along with theRutgers HaskinShellfish Laboratory, began an investigation into somenature-based armoring tactics and their applicability within theDelaware Estuary. Together they varied the configuration of ribbedmussels, coir-fiber logs and marsh grasses along the shoreline, anddocumented the performance of each arrangement.

|In 2011, they published the results of the study and createdthe Delaware Estuary Living Shoreline Initiative.This approach of using mussels and vegetation to restore livingshorelines has now been used for more than a dozen projects inDelaware and New Jersey.

||

Dry, dead trees dot Mount Eden,overlooking Flagstaff, Arizona. (Photo: Brady Smith/U.S. ForestService)

|Forest management to reduce floods in Flagstaff, Arizona

Flagstaff, Arizona, is no stranger to wildfires.

Unfortunately, fire is often just the first threat, asvegetation on the surrounding hillsides is a critical element ofnatural infrastructure for regulating both the quality and quantityof water flowing to the city. After a wildfire, severe rainstormcan send torrents of muddy, sediment-filled water rushingdownstream toward the 70,000 residents of the Flagstaff metroregion. While suppressing fires seems like the logical solution,suppression only is a short-term solution that disrupts naturalfire cycles and can lead to unnaturally high densities of fuelsources.

|After a particularly brutal fire-and-downpour cycle in 2010, theFlagstaff Watershed Protection Project was created tohelp reduce the risk of devastating wildfire and post-fire floodingin the nearby Rio de Flag and Lake Mary watersheds. By 2012 theproject successfully treated more than 70,000 acres of forest andhad been recognized as a leader in innovative and collaborativeforest management.

||

Sand dunes in Stone Harbor, NewJersy. (Photo: Stacy Small-Lorenz/National WildlifeFederation)

|Ecological approaches to reduce risk in Cape May County, NewJersey

How can a New Jersey barrier island resort town supportmillion-dollar beach homes, endangered beach-nesting birds andmaintain a Triple A S&P bond rating, all while receiving 25percent discounts on flood insurance?

The answer, according to Avalon, New Jersey, Mayor MartyPagliughi is investing in natural ecosystems.

|Avalon's beach and dune conservation strategy has grown into aproactive, decades-long effort toward property and environmentalprotection, serving as a model for other coastal New Jerseycommunities.

|The effort of communities such as Avalon in Cape May County topreserve sand dunes and other natural wetlands have shownsignificant returns. After Hurricane Sandy, Cape May communitiesthat had participated in U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dune and beachnourishment projects had relatively little storm and floodingdamages in places where wider beaches and deeper dune systemsprovided adequate buffers.

|Restoring and maintaining resilient ecosystems in thesurrounding landscape has brought benefits to local communities inthe form of storm, flood and erosion protection.

||

An overhead view of the GreatLakes. (Photo: Jeff Schmaltz/NASA)

|Stabilizing Great Lakes shorelines with native vegetation

Strong winds, high wave energy, occasional massive storms andseasonally thick ice make the Great Lakes a great laboratory forvegetated living shoreline projects designed for erosion andsediment control.

In places where high wave energy and ice continually disturbsediments and chew away at lake edges, vegetated living shorelinescan often be more naturally durable and resilient thanhuman-engineered hard armoring.

|The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration haspartnered with the GreatLakes Commission and local communities to stabilize shorelinesand restore wetlands with native habitat at a number of former sawmill and industrial sites. More than 33 acres of wetland and 13,000linear-feet of hardened shoreline have been restored so far. NOAAsays the $10 million investment in restoration efforts at MuskegonLake project will generate $66 million in economic benefits,including:

|• $12 million increase in propertyvalues.

• $600,000 in new tax revenues annually.

• More than $1 million a year in new recreational spending inMuskegon.

• 65,000 additional visitors annually.

• An additional 55 cents in the local economy for every federaldollar spent.

Marsh monitoring. (Photo: ChrisHilke/National Wildlife Federation)

|Shared ecosystem and community resilience in coastalMassachusetts

Vibrant coastal communities along the Great Marsh in Massachusettsare at risk from the threats of rising sea levels and increasinglypowerful coastal storms.

The Great Marsh plays a significant role in buffering nearbycommunities from the impact of the same coastal storms andnor'easters that threaten it.

|The Great Marsh Resiliency Partnership is workingto strengthen the coastal towns and the marsh itself, with supportfrom the U.S. Department of Interior Hurricane Sandy CoastalResiliency Program. The broad-based project partnership, whichincludes NationalWildlife Federation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, several universities,Massachusetts state agencies and a number of local environmentalnonprofits, are working together to reduce vulnerabilities andprotect key assets through implementing nature-based measuresdesigned to work at near-, medium- and long-term timescales.

|To address near- to medium-term threats of sea-level rise andcoastal storms, several ecological restoration efforts are beingcarried out, such as stabilizing existing dune systems by plantingnative dune flora and fencing in dunes to decrease trampling andother disturbance. Native vegetation is also being restored tohundreds of acres of marsh to help stabilize the ecosystem andbolster its capacity to provide flood protection.

||

Marsh restoration in Jamaica Bay,New York. (Photo: Don Riepe/American Littoral Society)

|Hybrid approaches to protect New York’s Jamaica Bay

New York City's Jamica Bay faces many challeneges in the yearsafter Superstorm Sandy, which caused 13 feet of storm surge and $19billion in damage in the area.

As a result, building resilience in the face of rising seas andstrong coastal storms has become an urgent matter in thelowest-lying part of the city.

|At the request of the city, the Nature Conservancy conducted an extensivebenefit-cost analysis of four resiliency options for the HowardBeach neighborhood in Jamaica Bay. The planners found that hybridapproaches of varying levels of traditional hardinfrastructure along with green infrastructure by far provided thegreatest risk reduction and avoided losses from a 100-yearstorm.

|The best hybrid option considered had a benefit-cost ratio 8-16times higher than the green infrastructure-only options, providingan estimated $662,000 in ecosystem services while avoiding $466million in damages to Howard Beach alone. In addition, hybridoptions offered reduced maintenance costs compared with only hardinfrastructure.

|New York City has made a significant commitment to climateadaptation, as outlined in its landmark 2013 "PlaNYC," with Jamaica Bay at the epicenter of coastalresiliency efforts. Taking into account the results of theconservancy's study, the Jamaica Bay plan includes a mix of stonebulkheads, living shorelines and restoration and creation ofwetlands and reefs.

|Related: Harnessing nature as a first line of defenseagainst disasters

|Click here to view our full coverage on disasterrisk and recovery for Hurricane Season2016.

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- All PropertyCasualty360.com news coverage, best practices, and in-depth analysis.

- Educational webcasts, resources from industry leaders, and informative newsletters.

- Other award-winning websites including BenefitsPRO.com and ThinkAdvisor.com.

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.