Claims files end up in litigation for a variety ofreasons. Unless the reason for the litigation was intentional onthe part of the insurance company or self-funding entity, thelitigation may indicate unsatisfactory service by the claimsdepartment or an individual adjuster. Litigation is an extraexpense on top of the value of the claim, unless the basis for thedispute was legitimate and unavoidable.

Claims files end up in litigation for a variety ofreasons. Unless the reason for the litigation was intentional onthe part of the insurance company or self-funding entity, thelitigation may indicate unsatisfactory service by the claimsdepartment or an individual adjuster. Litigation is an extraexpense on top of the value of the claim, unless the basis for thedispute was legitimate and unavoidable.

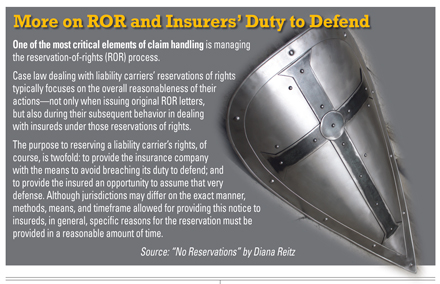

Why do claims files end up in litigation? There are a number ofreasons why an insurer may elect to litigate a claim. The first isthat there is a coverage dispute and the insured does not agreewith the insurance company that the coverage does not apply to theclaim. In such cases, the insurer may file a lawsuit with the courtrequesting declaratory relief, even if the insurer is actuallydefending the claim under a reservation of rights (ROR). The courtwill then review the claim and the coverage and look for the“eight-point match,” under which the “four corners of the policy”must match the “four corners of the claim or lawsuit.” If they donot match, then coverage does not apply—or at least it does notapply in totality. The parties must then agree as to what iscovered and what is not covered as well as who will pay fornon-covered parts of the claim. In a good claimsinvestigation and negotiation, however, those factors should havebeen determined and agreed upon without the court's help. When theauditor is reviewing a claim in litigation for declaratory relief,he or she should look for evidence that the adjuster sat down andreviewed the policy with the insured, seeking advance agreementthat the coverage did not apply or applied to only part of theclaim. If that is missing, then the file was not welladjusted. It requires a very good and experienced adjuster to beable to do this correctly and to document any “non-waiver”agreements reached with the insured in a formalized and officialway.

|Source of Coverage Disputes

Coverageissues can arise from many causes involving almost any aspect ofthe policy. The claim may involve a question of whether the partiesagainst whom the claim is being made are insured under the terms ofthe policy or by virtue of some contract. The dispute may involve acondition, such as late notice or, in a “claims made” policy,determination of when the insured first knew about the claim andwhether it was made within the time prescribed by the policy. Theclaim may not fit—or may not totally fit—the insuring agreements.Many lawsuits against insureds are filed for financial damages.Financial damages are neither bodily injury nor property damage,except to the extent of special damages or loss of use of physicalproperty. Perhaps the most common source of a coverage issue is anexclusion. If a loss is clearly excluded, then there is nocoverage.

The problem is that many claims or lawsuits “fall in thecracks,” where part of the claim may be covered but other partsexcluded. Plaintiff attorneys love to add as many counts to theirlawsuits as their imaginations can dream up—and often they are onlycreating problems for themselves because what they may allege, tomake the lawsuit sound more vicious, may be an excluded loss. “Thedefendant viciously and intentionally rammed his automobile intothe plaintiff's vehicle when the plaintiff stopped for the redlight.” Really? It's a simple rear-end collision, but now it isalso a coverage issue, because intentional injury or damage isexcluded.

| Now, what does the adjuster do with such a lawsuit? He orshe could call the insured and say, “Sorry, this lawsuit is notcovered. A denial letter is in the mail.” That would make quickwork of it—and would result in a lawsuit. Or the adjuster couldcall the insured and explain that the way the lawsuit is wordedcreates coverage issues. Since the insurer needs to act immediatelyin the insured's best interests, it would send an ROR letterreserving the right to deny coverage if the allegations turn out tobe true—but in the meantime the investigation would proceed and theinsured would be defended. Then the adjuster would proceed toinvestigate and, in 99 percent of the cases, find that theallegations of an “intentional act” were not true.

Now, what does the adjuster do with such a lawsuit? He orshe could call the insured and say, “Sorry, this lawsuit is notcovered. A denial letter is in the mail.” That would make quickwork of it—and would result in a lawsuit. Or the adjuster couldcall the insured and explain that the way the lawsuit is wordedcreates coverage issues. Since the insurer needs to act immediatelyin the insured's best interests, it would send an ROR letterreserving the right to deny coverage if the allegations turn out tobe true—but in the meantime the investigation would proceed and theinsured would be defended. Then the adjuster would proceed toinvestigate and, in 99 percent of the cases, find that theallegations of an “intentional act” were not true.

But there is that one percent of cases where it might be true.In such a case, the insurer may elect to take to court the evidencethat the insured knew the plaintiff, that he was angry with theplaintiff and did intentionally ram the plaintiff's auto with theintent to injure the plaintiff—and seek declaratory relief thatfurther defense is not owed.

|A Typical Scenario That Could Result inLitigation

An insured collides with another vehiclein an intersection, and the other driver is seriously injured. Theinsured has a $1 million policy limit. The nature of the injury,considering its permanency, might be worth $250,000, but there is adispute over who had the right-of-way in the intersection. Thestate has a modified comparative-negligence law. If the otherdriver was at least 50 percent at fault, his claim is barred. Butthere is some indication that the other driver, while partly atfault as he had the last clear chance to turn out of the insured'sway, was less than 50 percent at fault—maybe only 20 percent or 30percent at fault. The other driver's attorney alleges that theinsured was 100 percent at fault and that the claim is worth wellover $1 million.

This is a typical kind of claim that ends up in litigationbecause the parties cannot agree on the facts. How much is theclaim really worth? How much did the claimant actually contributeto the accident? Here is where an auditor can really earn his pay.What did the adjuster do about the dispute? Did he throw up hishands and say, “So sue me”? Or did the adjuster fully investigatethe facts of the accident, going to the scene and looking at whatis known from statements of the insured, the claimant, witnesses,and the physical evidence from both perspectives? Did the adjusterexamine the vehicles or retain an expert in accident reconstructionto try to figure out the physics of the accident? Maybe bothparties were distracted—the insured busy talking on a cell phone,while the claimant was looking for an address and was inattentive.If there were skid marks, where did they start, and was thatlogical for either explanation?

|Did the adjuster fully investigate the injury? Were timelinesprepared showing the claimant's medical history and any priorinjuries that might be an offset to the new injuries, or trackingfrom the time of the accident to the arrival of EMTs and theambulance as well as arrival at the emergency room and firsttreatment? Was there any delay that might be considered acontributory factor, perhaps even malpractice? Misery and claimsboth love all the company they can acquire. Did the adjusterarrange for an independent medical examination of the claimant oncethe medical information was received and a degree of permanentinjury stated?

|Then, if all this was done and the factorsdiscovered were favorable to the insured, did the adjuster sit downwith the attorney and discuss the facts? Today it is almost unheardof for an adjuster to actually meet with a claimant's attorney anddiscuss the claim. If the attorney is sitting with a file a footdeep and the adjuster has a file that has only a police report andthe medical bills in it, the adjuster will not be able to correctlyevaluate and reserve the file and conduct a reasonablenegotiation.

|Litigation is costly to both sides. If the adjuster has properlyinvestigated the facts as to coverage, liability, and damages, thenevery attempt to resolve the claim without litigation should bemade. Few insurers today allow their adjusters to do that. Instead,there is a phone call or two, an offer, counterdemand, new offer,and a “take it or leave it” new demand followed by a delay inresponse while the reserves are updated. If this is what theauditor finds, then it is most likely the claim manager'slimitations on the adjuster rather than the adjuster's own lazinessthat will be the cause of that lawsuit.

|The 'Tripartite' Relationship

It is oftendifficult for younger claim representatives and adjusters tounderstand the various aspects of claim litigation. Coveragedisputes are one thing; but disputes over liability and/or damagesare perhaps more common in either personal lines orcommercial-liability lines of insurance—especially where issues ofcontributory or comparative negligence are involved. A liabilityinsurance policy generally includes, as a supplement to the policylimits, any outside investigation and defense costs. The insurerowes the insured a defense of any claim or lawsuit against theinsured, if the coverage applies.

The insurer also has the right to settle or defend as it decidesis appropriate, even when such a settlement would require paymentof any deductible by the insured. The insurer has the right tosettle a claim, whether it is owed or not. The insured—unless theinsurer proceeds under an ROR or there is a “consent to settle”endorsement—must accept the insurer's defense and decision tosettle or litigate. If the decision is made to defend, it is theinsurer that selects the defense counsel.

|That should be the best defense counsel for the jurisdiction andthe type of claim involved. However, while the insurer selects andpays the defense counsel, it is the insured who is that defenseattorney's client—not the insurance company. Therefore, theattorney must provide the best defense of the insured possible,subject to the insurance company's ultimate right of decision as towhether to settle or defend.

|One aspect that the auditor must always examine is theanticipated value of the claim as compared with both the reservesset for the claim and the policy limits. If the file reflects thata “more than policy limit” demand has been made, has the adjusterissued any sort of excess letter to the insured, warning that theclaim's value might exceed the policy limits? Does the insured haveother insurance? Has the adjuster identified any co-tortfeasors orprincipals who might have other applicable insurance? If not, theadjuster is flirting with a potential “bad faith” claim, should thecase go to trial and the verdict exceed the insured's policylimits.

|Auditing Litigation Management

Too manyinsurance companies and adjusters simply abandon claim litigationto the defense counsel they have hired to defend the insured andlet the attorney manage the litigation. If the auditor detectsthis, it is a serious matter. The claim management team is “incharge” of overseeing what adjusters do. If adjusters abandonlitigation to attorneys, the costs are going to be far higher thanif the litigation was properly managed.

It is comparable to a patient seeing a doctor.The doctor makes a diagnosis but suggests a variety of expensivetests to confirm or rule out the diagnosis, partially out of fearthat if the battery of expensive tests are not run, the patientmight later make a malpractice claim. But every patient must be hisor her own medical manager, asking for an explanation of why eachsuggested test is needed and deciding whether to proceed. Apatient, after all, can say “No.” If the patient doesn't, thensometimes the patient's insurance company may have to say “No.”

|Likewise, the attorney must provide the best defense for theclient, the insured policyholder. But it is not always necessary todepose everybody in town and obtain five tons of documents if theclaim does not warrant such. Therefore, the adjuster needs to beinvolved in the day-to-day litigation management, with the statedobjective of resolving the dispute as quickly and cheaply aspossible.

|What should an auditor look for? First, it should be determinedwhether the insurer sees the claim as one that should be settled orone that should be disputed vigorously. If the claim is owed, and thedispute is only over how much it is worth, perhaps the lawsuit wasfiled only to stay the statute of limitations or to give anegotiating edge to the claimant. The only defense needed in such acase is an extension while the adjuster continues to negotiate, orelse the filing of an answer to prevent default while the adjustercontinues to negotiate. If the adjuster can negotiate a settlement,then the basic costs of defense—which can easily exceed $50,000 to$100,000—can be avoided.

|Weighing the Motion's Merits

Onthe other hand, if the claim is one that the adjuster and the claimdepartment management has determined is one for defense, then theauditor must look at all the aspects of the defense to see if theadjuster is properly managing it. It is the attorney who mustmaintain the day-to-day control of the case, but it is the adjusterwho is basically in charge of that “settle or defend” option.

The first aspect to check is whether the proper venue is beingused. If the case is in state court, should it be in federal courtor vice versa? Has the adjuster reviewed with the defense counselthe defense and plaintiff interrogatories and motions to produceand assisted in obtaining information that may be required? It isgenerally cheaper for the adjuster to do this than to have theattorney's paralegal do it. Have the defense's interrogatories beenreviewed and suggestions offered of additional information thatshould be obtained? At this point in the litigation, the adjustermay be far more familiar with the facts of the case than thedefense attorney, even if the adjuster's file waswell-documented.

|What sort of motions has the attorney suggested, and has theadjuster considered the merits of each? Every motion filed willrequire response by the plaintiff's side, making the case moreexpensive for both. If the reason for the litigation is a stubbornplaintiff that even his or her own attorney cannot persuade, abarrage of discovery can often help in making that plaintiff “seethe light” and capitulate. Aggressive defense can leave the otherside whimpering, and that can be an opening for reasonablenegotiation.

|Is mediation or arbitration being considered? Have there beenmeetings between the parties, and was the adjuster there? If therewas mediation, did the adjuster have sufficient authority tosettle? If not, the event was a waste of time and money. If trialis considered, then what is the defense attorney's opinion of theopposition's attorney, the judge and the jurisdiction? If it isunfavorable to defense, has any settlement offer been made?

|If both liability and damages are in dispute, then will thetrial be bifurcated, with liability argued first? These are allfactors the auditor must consider in reviewing the file. Simply bylooking for these factors, the auditor may be able to help move thecase from stalemate to a successful conclusion.

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- All PropertyCasualty360.com news coverage, best practices, and in-depth analysis.

- Educational webcasts, resources from industry leaders, and informative newsletters.

- Other award-winning websites including BenefitsPRO.com and ThinkAdvisor.com.

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.